Quick Menu

The summertime Torch Festival (火把节) is the best-known annual event in the Yi minority (彝族) calendar. With around 11 percent of the population, the Yi are the largest nationality in Yunnan. Their demographic contains about 25 sub-groups speaking five dialects. The Yi live all over the province except for spots in the southwest borderlands.

Not all of the sub-groups celebrate Torch Festival, and the Bai (白族) and Naxi (纳西族) minorities have a Torch Festival of their own, but most visitors think of it as primarily an Yi one, partly because of the massive publicity given to the extravagant celebrations of it in the Stone Forest (石林). In 2018, Chuxiong and Dali — the two major cities featured in this article — observe the festival on August 5.

Torch Festival origins

Several origin stories exist, and the one most common to the Yi living in central and western Yunnan attribute it to a hero's successful defense against the wrath of a jealous god. Accordingly, once upon an ancient time lived a famous Yi wrestler named Eqilaba, who had a reputation as being invincible. A jealous god in Heaven, determined to undermine his fame, dispatched a champion of his own to challenge Eqilaba. The challenger lost his life in the attempt.

Furious, the god sent a swarm of insects to destroy the Yi people's crops. Eqilaba organized the people and ordered them to light torches to drive away the pests. It worked and the people repelled the attack. Ever since then, on the twenty-fourth day of the sixth lunar month, the Yi stage Torch Festival to commemorate their victory. Village or city programs may include wrestling matches, bullfights and horse races to enliven the day, and then conclude in the evening by lighting torches and dancing around a bonfire.

Seeking out Torch Festival

I witnessed the Torch Festival of the Nuosu Yi in Ninglang County (宁蒗县) in the northwest on my first trip to Yunnan in 1992. The following summer I attended a multi-village celebration of it in the mountains northeast of the city. Some years later, when my research took me to other parts of the province, I tried to see it with the Huayao Yi (花腰彝) in Shiping County (石屏县). Just when all the participants, dressed in their finest, turned up at the venue it began to rain heavily and didn't stop until morning.

That was unlucky, but not unusual. The sixth lunar month is smack in the middle of the rainy season. A few years later, I scheduled another attempt, this time near Damaidi (大麦地) in Chuxiong Prefecture's Shuangbai County (双柏县). But a landslide had just recently cut off the village from the outside world. So instead I opted to take the earliest minibus to the city of Chuxiong and try to see the festival there. Chuxiong is an Yi Minority Nationality Autonomous Prefecture, which means the folks in charge of the government are Yi. They would be sure to sponsor something, I reckoned. The closer I got to the city, the more the skies cleared, though they remained dark to the south.

Chuxiong was never a popular tourist destination. Most travelers in the 1990s only knew it as a lunch break stop on the bus route from Kunming to Dali Old Town (大理古镇). By the end of the decade buses used the new highway and didn't even stop in the city. For travelers, Chuxiong had little of practical interest — a couple of nice parks, a single Buddhist temple, and a plethora of new, unimaginative, concrete buildings. A statue of Miyilu, the heroine of the springtime Yi Flower Festival, was the only visible minority culture motif in this capital of an Yi Autonomous Prefecture.

A trip to the Chuxiong Prefectural Museum

By 2000, all that had changed. The city now had a new prefectural museum — one of the finest in the province. Four floors in the central part of the complex were devoted to various aspects of local culture, predominantly those of the Yi. The ground floor displays had all the items used in traditional daily life — tools and implements, baskets and containers, hunting and fishing gear, hand-made clothing and musical instruments. There were also house models of traditional Yi abodes, as well as those built by Chuxiong's other minorities the Miao (苗族), Lisu (傈僳族) and Dai (傣族).

The second floor exhibits over fifty traditional clothing outfits, mostly women's, from the prefecture's Yi sub-groups, as well as those from other parts of Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan. The displays include spinners, winders, looms and accessories like jewelry and embroidered shoulder bags. The third floor features books composed using the Yi alphabet used by bimaw, or religious specialists. Also highlighted are grotesque wooden masks, painted gourds, lacquered bowls and other antiques. The fourth floor contains books on Chuxiong and the Yi.

It is not just an ethnic minority museum, however. Rooms around the center are devoted to other topics. One features the prefecture's fauna — its endemic reptiles, amphibians, birds, insects and mammals, as well as other extinct creatures of the past. Dinosaur skeletons found in Lufeng (禄丰) are included, as are the remains of some of man's ancient ancestors. There's a calligraphy room exhibiting elegant brushwork as well as thin pieces of wood shaped into Chinese characters. Another hall contains ceramic and bronze artifacts dating to the time of the Zhou Dynasty, with paintings beside them that show how they were used.

Chuxiong's huge Yi minority park

The other major change in the city around this time was the recently completed and elaborate park northwest of the city on the other side of the Longchuan River (龙川江). With the wordy name 'China, Chuxiong Yi Nationality Ten-Month Solar Calendar Culture Park' (中国楚雄彝族十月太阳历文化园), this was the new venue for Torch Festival celebrations. Previously, the they were held in the roundabout with the Miyilu statue mentioned above. But this was now covered by an overpass and the statue removed.

The park's name refers to the pre-modern Yi calendar that divided the year into ten, 36-day months. Each month contained three 'weeks' of twelve days, all named after different animals in the Yi zodiac. The Chinese also have a twelve-day cycle with each day named after an animal, but the two versions differ slightly — Yi pangolin day being one example.

It seems everything in the park was intended to be big and impressive. Enormous blocks of carved stone stood at the entrance, depicting dance scenes from the Yi 'Dressing Up as Tigers Festival'. These friezes were in turn flanked by a huge bronze drum replica. Dominating the rear of the park is a tall, carved column surrounded by smaller ones, all on top of a monumental edifice of walls and stairs.

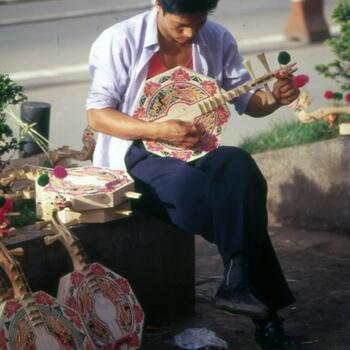

The city's Han, who form at least 90 percent of the population, also enjoyed Torch Festival as a holiday of their own. On the day of the celebration, red lanterns and vertical banners decorated shops and offices. Stages went up in Longjiang Park for performances by singers, jugglers and magicians, and street vendors were everywhere — some with Yi men selling 'moon guitars', gourd-pipes and flutes. Since the government-sponsored program would not begin until after dark, early arrivals from Yi contingents across the prefecture — dressed in their finest traditional clothing and ornaments — wandered the urban streets and parks.

Time for a bonfire

At sunset, people began heading for the park. The program was scheduled to start at 8pm, but was delayed until after 10pm, when the fireworks launched from tall buildings in the city center had already been illuminating the sky for some time. Then a group of Yi women in red jackets and turbans climbed onto the stage in front of the columns and lit their torches. They strode offstage to a big iron cauldron in the plaza as other Yi contingents followed them. The procession included a few bimaw dressed in fancy ritual garments and miters. The young women tossed their torches into the pile of kindling and soon a bonfire was blazing.

Performers still occupied the stage for a while — solo singers, duos, those performing comedy skits and groups of traditional Yi singers and musicians. Finally, the stage action concluded and the Yi sub-group contingents commenced ring dances around the fire. The activity continued until one in the morning.

Torch Festival redux in Dali

As mentioned, most Yi areas in Yunnan hold Torch Festival on the twenty-fourth day of the sixth lunar month. The exception is in Dali Bai Nationality Autonomous Prefecture (大理白族自治州), where the Yi follow the Bai custom of marking the holiday one day later. This gave me the chance to see it all again after the Chuxiong affair. I left in the morning and thanks to some serious detours caused by road repairs, the 38-kilometer trip took almost an entire day.

My destination was Yangbi (漾濞), a much smaller city than Chuxiong notable for its old bridge, traditional Muslim quarter, an indigenous-style mosque and its famous walnuts. The rest of it was a rather run-down but modern city with the only Yi symbol in sight being its own Miyilu statue. As it was and is an Yi-run county, its local government-sponsored Torch Festival celebrations, meaning sub-groups from all the county districts would be paid to come to the city for the event.

Rather than the bundles of long wooden sticks of Chuxiong, the torches here were mostly structures of colored paper organized into several tiers. They had pennants on each side, like the Bai torches, and stood at intervals in the streets. Dark clouds were already filling the sky when I arrived, making the torches' bright colors stand out. By the time I got my hotel room, night was beginning to fall and the procession to the central stadium was about to begin.

Four different sub-groups participated, all wearing distinctly different outfits. The least colorful of them dressed mainly in black and white with sparse embellishment. The men wore long-sleeved white shirts over dark pants and open black vests. The women wore the same shirts with sleeveless, knee-length black tunics trimmed in blue over black trousers, highlighted with wide white belts. Women of another sub-group wore knee-length, side-fastened tunics, blue on top and black on the bottom, with thick, multi-colored, appliquéd bands around the collar, hems and lower sleeves.

The female contingent from the western hamlet of Fuheng (富恒) wore brighter, flashier tunics and aprons, covered with appliquéd strips and embroidery. Complementing this were round black caps with a silver bands along the bottom and colored pompoms sticking up from brims. Their men wore plain white shirts and black pants.

Finally, the cast included the Nuosu Yi (诺苏彝) from the northern part of the county. I knew and had written about them my time in Ninglang County, but didn't know they also lived this far south. The women dressed in long, tri-colored skirts, vests and long-sleeved blouses, as well as the same very wide-brimmed hats as people in Ninglang. The men wore black turbans, embroidered vests and black woolen capes.

When all those in processions had filed into the stadium and taken up positions around the central torch, two Nuosu Yi youths, shirtless and in wide-legged trousers, beat drums and cavorted around the pyre. Then two of women came out to give a bowl of rice-liquor to each of the men charged with lighting the torch. Because it had been doused with paraffin already, the torch caught fire easily. One of the Yi groups then commenced dancing around the burning torch.

Soon it began raining, though that didn't dampen the dancers' spirits, especially the lead male wielding a long curved sword. When it got heavier the audience fled for shelter and the dancers finally stopped. After 40 minutes, the rain was just a slight drizzle, so the dancers and crowd returned and all the contingents got their turn. The torch had continued burning and folks added more paraffin-soaked rags to keep it going. In spite of the rain, the dances were quite vigorous and no one slipped on the wet pavement.

From the top of the bleachers men set off a series of fireworks. While not as plentiful as those in Chuxiong, they were quite spectacular and close to the audience. The dance groups occupied other areas of the stadium around the main torch and continued for another few hours. Out in the city streets, the torches that had been standing all day were now piles of cinders, while youths with mini-torches in one hand prowled the streets armed with resin to toss onto the torches to make them flare up whenever they met anyone in their paths.

Around midnight the celebration began slowing. The stadium emptied of dancers and observers. The last shops still open shuttered their doors. The kids with the flare-up torches ran out of resin powder. The revelry was over. It was time to retire, review memories of the day and sleep secure in the knowledge that, being Yi, they will be able to enjoy it all again the next year.

Editor's note: This article by author Jim Goodman was originally published on his website Black Eagle Flights (requires proxy). There you can find accounts and photos of Goodman's 40 years in China and Southeast Asia. Collections of his works — many of them about Yunnan — can be purchased on Amazon and Lulu. Goodman has also recently founded Delta Tours, where he guides cultural and historical journeys through Vietnam and Yunnan.

All uncredited images: Jim Goodman

© Copyright 2005-2024 GoKunming.com all rights reserved. This material may not be republished, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

Comments

Another good article by Jim Goodman. Note that he has made his home in Chiangmai for over 30 years. Chiangmai has become a tourist destination and/or visa renewal destination for many foreigners living in Yunnan over the past years and,knows a great deal about the history, temple iconography and other aspects of life of Chiangmai city and of surrounding areas.

Login to comment