Quick Menu

Before the tragic earthquake of 1996 devastated Lijiang (丽江), the old Naxi minority (纳西族) town of Dayan (大研古城) offered travelers a wonderful experience of traditional urban life. Concentrating my research on northwest Yunnan then, I explored the city on many excursions spread across several years, wandering down every street and lane in Dayan.

Dayan's Naxi rose later than those in rural areas. The first establishments to open were the noodle-makers and those preparing black bean pudding. People began setting up market stalls and opening shops around 9am. Women came to the streams to wash vegetables, men led pony-carts full of charcoal and firewood and shoppers started appearing shortly after.

The one activity missing was anything religious. No shrines or statues stood anywhere on the streets. The only religious building was the temple next to White Horse Dragon Pool (白马龙潭) in the town's southern quarter. It marked the spot where the Tang Dynasty Buddhist scholar Xuan Zang (玄奘), on his way to India to procure religious manuscripts, supposedly stopped to give his horse a drink. The modest temple, built in the eighteenth century, did attract occasional devotees who bought fish to set free in the pond.

Still influenced by Confucian traditions, the Naxi maintained their ancestral altars and made offerings to them at festival times. But even the surviving village temples, those that hadn't been converted into schools, were hardly active. The big monasteries were barely maintained at all. In general, the Naxi, in contrast to the Tibetans (藏族), Bai (白族), Hui (回族), Dai (傣族) and Bulang (布朗族), didn't seem very religious-minded.

Naxi history

Long before exposure to Buddhism or Taoism, the Naxi had established their own belief system, built on the propitiation of natural elements and the presumed existence of myriad unseen forces. Everything in the world was endowed with a soul and life-force of its own, including inanimate objects such as mountains, streams, fires, cliffs and stones. The ancient Naxi believed something or other controlled the weather, the rain and the wind, and so deified and gave names to these assumed agents. Lesser deities and spirits were associated with other natural phenomena. And to account for all that could go wrong in the course of a life, the Naxi identified more than 500 demons.

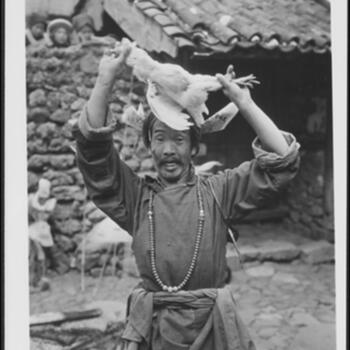

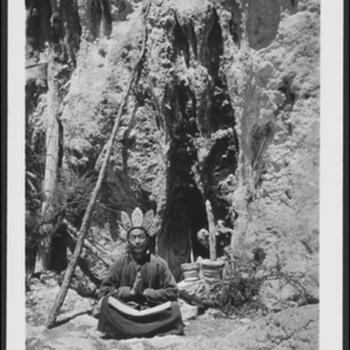

To deal with these pernicious spirits — and to properly honor or beseech the gods — a class of specialists arose within Naxi ranks. Known as a dongba, this holy figure performed a wide array of numerous and complicated rituals. To prompt his memory he used manuscripts in coded pictographs and performed rituals both privately for patrons and publicly for the welfare of the realm. These men were so much at the core of traditional religious practice that even today the original Naxi belief-system is known as the 'Dongba religion'.

A few of these rituals lasted several days and required recitations from over a hundred separate books. Among the most frequent were those propitiating nagas — the huge, dragon-like serpent spirits believed to be the invisible owners of the land. Ceremonies concerned with the expulsion of demons — varying greatly according to the type of demon and sometimes involving dancing while wielding swords — were common.

So too were rites for suicides, who were nearly always young couples whose parents had forbidden a marriage. Funerals were other important events, the most spectacular being those of a dongba himself. The highlight of a Dongba religious funeral was the display of a painted scroll twenty meters long and a recitation of a text explaining each of the illustrations at length.

In the old days, village dongba customarily wore large-brimmed felted wool or bamboo hats. Otherwise they did not stand out among other villagers. They lived in the same kind of houses, and while patrons fed them on the occasion of a right or ceremony, dongba did not receive any salary. The only social advantage was the prestige accorded by being one.

For rituals, they generally donned a five-lobed crown, called kho, with deities painted on each lobe. They employed thick, oblong cards with figures painted on them, called dzu, which they stuck upright in groups of seven, nine or 11 in bowls of rice placed in the middle of an altar. They also used wooden swords, called khobya, that were painted with pictographs. These they thrust into the ground next to streams to propitiate nagas, or into hillsides away from a funeral site. For some rites, dongba also made small figurines out of corn flour representing deities and demons.

The importance of Sanduo

The venues for these rituals could be anywhere within the village or outside by a stream or on a mountain. There was no Dongba-dedicated religious temple of any kind. The first temple in Naxi territory was to their own war god, Sanduo (三朵神). It was built in 784 under orders of King Yimoxun (蒙异牟寻) of Nanzhao (南诏国), the state that ruled over Yunnan at the same time as China's Tang Dynasty.

Lying at the foot of Jade Dragon Mountain (玉龙雪山), just below present-day Yufeng Temple (玉峰寺), the temple dedicated to Sanduo is called Beiyuemiao (北岳庙) — or 'Temple of the northern sacred mountain'. A statue of the god, dressed in white armor and a helmet, brandishes a white spear and sits astride a white horse. A manuscript inside contains prayers to the god, as well as the legends and exploits associated with him.

The most famous legend is of Sanduo's aid to Azong (阿宗), the last Naxi ruler prior to the Mongol conquest of Yunnan in 1253. The god appeared to Azong in a dream, complimented him as an "upright" magistrate and promised to help him on the battlefield. From then on, the god appeared whenever Azong went to war, "rushed furiously to the battlefront" and then disappeared in a storm afterwards.

After the Mongol conquest, Mahayana Buddhism gained a foothold in Lijiang with the construction of Jinshan (金山寺) and Donglin (东林寺) temples. Dabaoji Palace (大宝积宫) in Baisha (白沙古镇) village is its finest Ming Dynasty expression. Daoism found a place as well in Dayan and adherents built the Jade Emperor Tower Temple and the Royal Heaven Temple. The philosophy became popular among the literati and its Dongjing music (洞经古乐) became a canonized part of Naxi tradition.

The arrival of Buddhism and Daoism

The introduction of Buddhism and Daoism influenced Naxi painting as well, which rapidly evolved from the simple, almost crude pictographs of the dongba manuscripts to the sophisticated wall murals that graced thirteen temples in the Dayan area. The overall balance of the murals and the orderly disposition of their figures, reflected a more Han-Chinese tradition. Subject matter could be Mahayana Buddhist or Daoist themes. The vivid coloring, emphasizing red, gold, black and silver, also reflected a strong Tibetan influence.

Sadly, today most are gone. Nine of the temples fell to ruins and the other four were completely destroyed or badly vandalized during the Cultural Revolution. The outstanding extant example is at Dabaoji in Baisha Village. The main fresco depicts the Buddha achieving enlightenment. He is surrounded by haloed holy men and bodhisattvas that appear to be floating in the clouds. Other murals feature Tibetan lamas called dakinis — fierce deities and magistrates in hats and robes conversing together while elsewhere the Day of Judgment takes place. Vignettes of contemporary life, such as plowing or weaving, are portrayed in the margins.

Nearby Dading Tower also has some Qing Dynasty frescoes, mostly restored, except for the gouged-out eyes. The only other testimony to the expertise of classical Naxi painters is the smaller set of murals in the Shuhe Dajue Temple (束河大觉宫). Against a black background, the figures are skillfully painted in gold, red, black, white and yellow, with fine details on the faces and in the depictions of jewelry.

Lijiang's lamaseries date from the end of the sixteenth century, with the introduction of the Karmapa — or Red Hat — sect of Tibetan Buddhism. The earliest of these monasteries was Yufeng Temple (玉峰寺), built between 1579 and 1619 at the edge of the forest on the slopes of Jade Dragon Mountain. The great camellia tree there, which attracts so many during local festivals, was planted a century earlier. One of Yufeng's courtyards was built around this tree featuring carved doors and window frames, a pebbled courtyard floor in geometric designs and the remains of the original interior frescoes.

More dramatically sited is Wenfeng Monastery (文峰寺), high up on Wenbishan (文笔山), nine kilometers southwest of Dayan. Completed in 1733, it is isolated far above the nearest village, lying beside a forest and spring. Until 1949 monks came here to perform an unusual ascetic rite. Digging holes near the spring, they climbed into them and made them their residences for the next three years, three months, three days and three hours. During this period they never left their holes and spent the time meditating, chanting and otherwise purifying themselves. When they finally emerged, they were supposed to be endowed with supernatural powers, such as the ability to fly.

Puji Temple (普济寺), all but hidden in a forest five kilometers northwest of Dayan, was the third Karmapa lamasery, originally built in 1771. Two great crab-apple trees with twisted trunks stand in the main courtyard. Time, weather and neglect have reduced most of the exterior wall murals to mere traces and outlines. But the interior furnishings are in better shape. They feature painted religious scrolls — otherwise known as thangka — which are bright silk banners and various images of the Buddha and important Tibetan lamas.

The other two Karmapa temples were Zhiyun (指云寺) on the shores of Lashi Lake (拉市海), and Fuguo (福国寺), above Nguluko (玉湖村), the northernmost village on the Lijiang Plain. Zhiyun Temple has been turned into a school and the buildings of Fuguo Temple were removed to Black Dragon Pool Park (黑龙潭公园) in Lijiang. The very ornate entrance gate, Five Phoenix Tower (五凤楼), today graces the southern end of the park.

After 1949 the lamasery residents were reduced to a bare minimum. Proscribing their ceremonies, the government co-opted Naxi holy men by making them village chieftains. Beyond the Lijiang Plain though, the Dongba tradition survived. This was especially true, if not very openly advertised, in communities near Baishuitai (白水台) and in southern Shangri-la County (香格里拉县).

The Naxi over the last 40 years

Around Lijiang during the 1980s, hardly any former dongba were still alive. The rituals did not revive, but the local government set up a Dongba Research Institute near Black Dragon Pool Park and hired former holy men to translate the pictograph manuscripts that had survived. A museum next door exhibited some of these books, plus the hats and robes, wooden swords, funeral paintings, drums, figurines and other items associated with the old Dongba rituals.

Like other minority nationalities in Yunnan, the Naxi were reviving their traditions, but that didn't necessarily include whatever religious piety they had once had. While in areas far from Lijiang, like Baishuitai or Dazui (大咀) — the Naxi village on the northern shores of Lugu Lake (泸沽湖) — the Dongba tradition continued. However, not many young men were taking up the role. No new dongba shamans appeared in villages on the Lijiang Plain. The mind-sets of the Naxi people had moved beyond the animism and nature-worship that once formed the essence of their traditions.

None of Lijiang's lamaseries regained their former popularity. In the 1990s, Zhiyun Temple was still used as a school. Lay caretakers looked after Puji Temple and two septuagenarian monks lived at Wenfeng monastery. Only Yufeng Temple had been able to recruit any new novices. About twenty were living there when I conducted my research. That small number doesn't compare to the hundreds in residence before 1949. The new mood of official tolerance meant monks could preach again and a Tibetan huofo — or reincarnated lama of the Yellow Hat order — set up in Dayan to instruct Naxi in Tibetan-style Buddhism. But after two years of scant success, he departed.

Traditional festivals, however, came back into vogue. The Naxi celebrate the major Han festivals, but sometimes with special features. Their new year rites include an outdoor sacrifice to heaven and during Mid-Autumn Festival for venerating ancestors, they hang big, fancy lanterns on their doorways. On the first day, with firecrackers and hot-air balloons, the Naxi salute their ancestors and invite them back into their homes. On the second night they place small paper lanterns — usually lotus-shaped with a candle in the center — into the streams. And on the third night they inscribe their clan names on paper and make sacrifices of fruits and grains to their ancestors.

The biggest traditional event remains Sanduo Festival. It is held on the eighth day of the second lunar month to honor the Naxi's chief indigenous deity. In the morning people hike up to the temple dedicated to Sanduo to leave offerings. Afterwards they ascend to Yufeng Temple, where the old camellia is in full bloom, to pose for photographs. Next, they may make a stop in the compound where the lama is performing his rituals for the occasion. Upon departure, people typically head for a spot in the woods or on a nearby hill to have a leisurely picnic.

Back in Lijiang in the afternoon, they may form up for ring dances in one of the public squares. Sometimes traditional orchestras are contracted to play for the day and much feasting ensues beginning around sunset. Ostensibly a religious festival, the day is actually completely concerned with celebrating Naxi identity, and people relish it as a time for socializing and public entertainment.

Editor's note: This article by author Jim Goodman was originally published on his website Black Eagle Flights (requires proxy). There you can find accounts and photos of Goodman's 40 years in China and Southeast Asia. Collections of his works — many of them about Yunnan — can be purchased on Amazon and Lulu. Goodman has also recently founded Delta Tours, where he guides cultural and historical journeys through Vietnam and Yunnan.

Uncredited color images: Jim Goodman

Black and white images: Joseph Rock courtesy of Yenching Library at Harvard University

Comments

Great stuff Jim. Thanks.

Login to comment